Two Uncles: Two Heroes

Murray McCheyne Thomson OC

The death last spring of my uncle, Murray Thomson, prompted me to reflect about two extraordinary uncles who had a profound effect on me, their families, and our country. Although one was the first to die in his family when he was not yet 21, the other was the last to die in his, at the ripe old age of 96. Despite this gap in age, both shared some commonalities of character, circumstances and commitments.

WO II Donald Cameron Plaunt

Their parents chose names for them which reflected their family traditions: Murray McCheyne, after an inspirational Scottish preacher and Donald Cameron, after a revered relative in the Plaunt family.

Both men had strong foundations based on remarkable families. Both fathers grew up on farms in rural Ontario: Murray’s father, Andrew, south of Owen Sound while Donald’s father, WB (Bill), was raised off the Opeongo Trail, west of Renfrew. Their mother’s background varied. Donald’s mother, Mildred Hicks, was born in Bracebridge, Ontario. Since her father was a jack-of-all-trades, the family moved frequently as he looked for work. Murray’s mother, Margaret MacKay, had a more difficult beginning as her mother died shortly after she was born. Despite these challenging beginnings, both women became motivated, resourceful and compassionate women.

The Thomsons had three boys (although one died shortly after childbirth) and five girls, while the Plaunts had four girls and two boys. Murray and Donald, were both born in 1922 and were the second youngest in their respective families that meant special attention from older siblings. As a result they grew up in loving and supportive families.

Margaret MacKay, whose father was the Foreign Missions Secretary for the Presbyterian Church of Canada, met Andrew Thomson at U of T. He attended divinity college in preparation for his calling as a missionary in China. After graduation, they married in 1906 and travelled to the southern China province of Honan. For the next thirty-five years they served their Christian community in Taokow. Violent war-lord battles and roaming brigands threatened the rural Chinese making it difficult for the missionaries to help their impoverished charges.

Because of the isolated location, their children were sent to boarding schools in China or Japan and then to Toronto to complete their education. Their mother kept in close contact with each child with regular letters (with seven carbon copies) to each. Being so far away from their family created a strong self-reliance and a concern for one another. In was in this setting that Murray gained a concern for humanitarian issues, strong family values and an incredible commitment to peace.

Murray (L) of his maternal grandfather in 1926

Donald grew up in very different circumstances, but like Murray, was strongly influenced by his father’s profession. WB Plaunt left school after grade 8 and used his mathematical and business talents to become a highly successful entrepreneur in the lumber industry. Initially, he worked on the family farm in summer and in logging camps in the off-season. While working for the Eddy Brothers in Blind River he met Mildred Hicks where she taught in a one-room school in nearby Thessalon. They were married in 1912 after she completed a nursing degree at Guelph. After three moves throughout Northern Ontario, they ended up in Sudbury with six children in 1925.

Donald (L) with his family in 1928

Like the Thomsons, the Plaunt children were separated from their parents during their formative years as all their children attended boarding school. Both families used their summer vacations to spend time together: the Plaunts in a small sawmill village alongside the CPR and the Spanish River, and the Thomsons at Peitaiho Beach on the Pacific Ocean. Time to live in an isolated setting bonded the two families into close-knit units. Although the Plaunt sawmill closed in 1940, their father established a family camp on Lake Pogamasing which their descendants still share today. Given the scattered global location of the Thomsons family reunions became a regular tradition to unite the far-flung members. Ironically, three of their gatherings were as guests of the “other uncle’s” family, the Plaunt community on Pog.

Different settings, different professions but above all, four strong parents and a commitment to family. And, as the saying goes, “the fruit doesn’t fall very far from the tree.”

Given Donald’s shorter life-span he did not get much of an opportunity to develop his talents into a career. Instead, he followed his sense of duty to enlist in the Air Force at the end of secondary school in May, 1941. After completing two levels of pilot training in Ontario, he was off to England in March, 1942. By December, he was piloting the Lancaster bomber. Tragically, he died in his 11th mission on a raid over Essen on March 12, two months shy of his 21st birthday.

Coincidentally, Murray also enlisted in the Air Force, but later in 1944. However, the war ended before he was called into active service. His “service” was to come in a different role: in multiple humanitarian causes: adult education, the Friends, CUSO, United Nations, several peace movements and especially, his drive to abolish nuclear weapons. He actively worked until his death at 96 with two other Order of Canada recipients, Douglas Roche and John Polanyi, to petition the government of Canada to pursue a policy of nuclear disarmament. Although they had over Order of Canada 1,000 signatures on their appeal, there has been no official response as of yet.

Both uncles were engaging, enthusiastic, humourous and talented individuals. Both were good athletes; Murray played on his college basketball team while Donald was the goalie for his high school hockey team. Each had a beaming smile and outward friendliness which endeared them to all they met. I have no record of Murray’s early humour but I do have a few amusing anecdotes of from Donald’s letters, especially to his sisters. At ten years of age he wrote to his sister Helen:

I love you; I love you I love you but don’t let that werry you.

I had three mistakes in spelling bute don’t let that weorry you ether.

I runded out of ink but don’t lets that worry you neither.

At seventeen, he teased his younger sister Jean: A very happy birthday to you! Coming right along aren’t you? Well now just imagine little Jean Plaunt all of sixteen years! Well there is one happy thing, you certainly have them buffaloed on that old adage, ‘and never been kissed’. His letters to her were sometimes of a teasing nature, offering brotherly advice, but always demonstrating a strong concern for her.

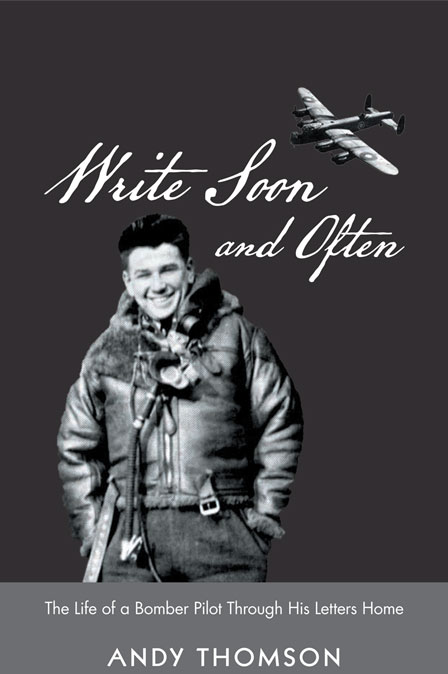

Donald’s 150 letters to his parents were informative about his training, developments in the war, Sudbury and Ridley friends he met overseas, and family matters, especially about his young nieces and nephews. He wrote frequently and longed for more letters which reflected an under-current of homesickness with his constant request to “write soon and often.”

Murray was known for his buoyant personality, groaning puns and quick and amusing humour. On a few occasions when he came to Toronto he stayed with Mandy and me. We always knew when he was awake because we could hear him singing old Broadway musicals. Our morning conversation switched from his current concerns to humorous anecdotes. He was always in a upbeat mood. It is difficult to remember examples of his humour, but fortunately, he wrote a group of limericks that roasted my father on his 70th birthday:

A budding young doctor called Mac

First practised his art in Levack

Where a cute nurse named Plaunt

Her attractions did flaunt

And caught Mac, in a shack, in Levack

Murray used his literary talents in many ways: some serious, as in books and proposals for the organizations he worked for, and most especially for one closest to his heart: his family. Given the global spread of the family – China, Australia, Japan, Germany and various places in Canada – Murray penned this frequently sung family ditty in 1989 that we sang at many reunions (verse one of six).

The Gathering of the Clan (to the tune of John Brown’s Body)

From Engelberg to Edmonton, from Sudbury and the Soo,

From Hanover and from Ottawa and Alexandria, too;

From Brampton and Down Under and from far away Japan,

We’re getting it all together with a Gathering of the Clan.

Chorus:

Peitaiho to old Toronto, Peitaiho to old Toronto,

Peitaiho to old Toronto Mother dear,

We’re getting it all together, here!

Family get-togethers were led by our enthusiastic, youthful uncle; providing music as a violinist and leader of our family quintet; beating off the Clugstons chess challenges; kibitzing with his three granddaughters; and on a more serious side, telling stories about his parents work in China. Along with his books on peace and disarmament, he wrote a biography of his father’s work in China, A Daring Confidence and a subsequent collection of his mother letters in Mother, God Bless Her. In his later years he started an internet Good News Service to document some upbeat stories from around the globe, the last one published just two months before his death. It mirrored his personality: keep it positive, don’t give up hope and persevere!

Both uncles possessed a strong sense of adventure and a natural curiosity about the world. At 16, Donald was off on a school trip to Europe in the summer of 1939. He kept detailed notes in a diary and in letters regarding the historical and literary places he visited. He was also very observant about a more current issue: in every country he visited “there was a preparation for war.” He arrived home two weeks before the outbreak of war on September 1.

Murray’s adventures came from his family situation. He attended boarding school in China and Japan and travelled with the family for the annual summer vacation to Peitaiho Beach. On family furloughs, he returned to Toronto and after he was through elementary school, attended North Toronto Collegiate and U of T. Once employed, he worked in a variety of places such as Saskatchewan, India, New York, Thailand, Toronto and Ottawa.

Murray’s parents’ commitment to serve others was obvious in their missionary profession. Donald’s parents also were very considerate of their social obligations, but in a different way. For his workers, WB offered profit sharing to his log cutters and annually eliminated company-store debts to his mill workers. He was also chair of the Sudbury War Bonds Committee and was a generous contributor to many Sudbury charities. Margaret Thomson, too, was actively involved in women’s groups in China and Mildred Plaunt worked in local charitable organizations, especially during the war.

Donald’s concern for others was evident in his attitude towards his seven-man bomber crew. When Donald learned that the three-year old daughter of his rear gunner was going to have a sparse Christmas, he wired his mother to send a Christmas box for her and gave her a box of his favourite chocolates which was meant for his crew. He frequently requested cigarettes for his crew, although he never smoked.

Whenever Andrew Thomson came to Sudbury, WB Plaunt took him speckled trout fishing, a passion they both shared. The two fathers also shared a serious social concern: the consumption of alcohol among young people. Murray’s father was so concerned he wrote a book entitled Alcohol or Christ while Donald’s father offered his youngest son and daughter $500 if they didn’t drink or smoke until they were 21.

I don’t know at what age Murray tasted his first drink, but I know my father was so sensitive to the issue that he held two receptions for my sister’s wedding, first in a dry location for his family believing they were all teetotalers. But, when the party moved to a wet location, they all came. Donald developed a reputation as a non-drinker and he sailed through high school and his Air Force career without a drink, or smoke, and was two-months shy of the goal of collecting $500. His father had already bought him a war-bond knowing his son’s commitment was firm. While all his buddies were out at the pub, he was home writing letters.

I met my Uncle Donald once when I was five months old. He was home on his last leave before heading overseas. Those who knew and loved him – parents, siblings, and friends – felt his loss deeply. After the Plaunts received the news that Donald was “missing, and presumed dead,” she wrote her mother: Don’t feel too badly. He lived a full happy life and perhaps accomplished more in his almost 21 years of living than some people do in a lifetime, and if he, and other lads before him, were not ready to go and die, where would we all be? He chose to do this and he did it in his own way.

After reading all his letters and writing his biography Uncle Donald became more like one of my own children. I still feel his loss. But at least I was able to record his life for others to know what a wonderful young man he was becoming, as were so many of the other 45,000 Canadians who never returned.

We were fortunate to experience Uncle Murray in a multitude of roles and situations. He was a delight to be with – we just called him Mo – and our family was so proud of the contribution he made to humanitarian and peace efforts. While Murray was training to become a pilot in 1944, his mother wrote to her family after a visit with Murray’s good friend Finlay Mackenzie: Finlay plays the piano so well and Murray had his violin. I could not help wondering how long it would be before I should hear them play again. But one should not expect the worst to happen. We pray that these dear lads may be spared to have a share in building the new World Peace.

How prophetic.

His family, friends and colleagues were fortunate to witness the incredible role Murray played in working towards world peace. We attended his awarding of the Pearson Peace medal by the Governor-General Ray Hnatyshyn in 1990, but were unable to experience his acceptance of the Order of Canada in 2001 due to attendance restrictions. We attended his 90th birthday celebration in Ottawa in 2012 and he used the occasion to discuss nuclear disarmament with 125 of his associates, friends and family. It was an honour to be included, especially to hear him play “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” on his violin with back-up provided by Helene Bieman, a resident pianist, and later, with his favourite band, The Grateful Not-To-Be Dead.

We are less fortunate for the loss of two uncles who gave so much in the cause of a more peaceful world: one who fought to end the war, the other who fought to keep the peace.

Murray Thomson 1922 – 2019