THE LIFE OF A BOMBER PILOT

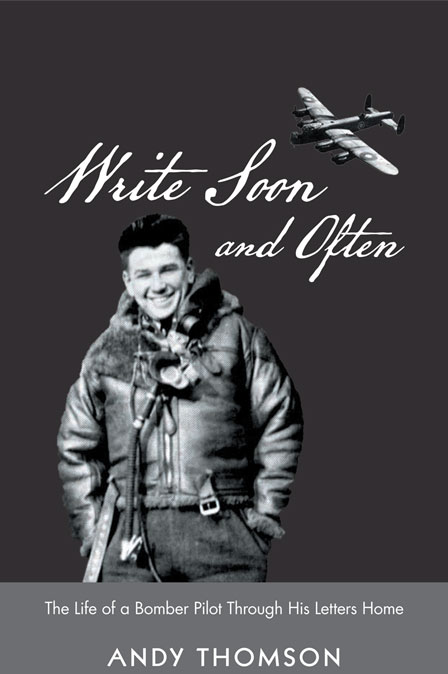

For years I have been posting a photo memorial (see Remembrance Day, 2017) to my uncle, Donald Plaunt, who was killed in the Second World War. I have now completed a biography of his life primarily based on letters he wrote home. Below are a few excerpts from the book.

SUMMARY

There are many compelling stories written by veterans about Bomber Command. What makes this pilot’s story unique is that it is told in his youthful voice, selected from 150 letters he wrote home. Peppered with his amusing sense of humour, his letters covey a very personal and colourful narrative, ranging from tales of his Air Force training, the events of the war, the people he cared about, and the issues that bothered him. It is a story about youth and hope as we follow his journey from a carefree and somewhat entitled rookie pilot to the generous and proud captain of a Lancaster crew. It is also a story of sorrow that explores the heartbreaking impact of his death on his family, when he, like so many other young men, did not return home.

EXCERPTS

I knew I was destined to write this story after an incident on Parliament Hill in 1969. While a high school history teacher, I organized a student field trip to Ottawa to give my students an opportunity to visit our federal government and national museums. After attending a session of the House of Commons, we walked up to the Peace Tower, the iconic bell and clock edifice, which was built as a memorial to commemorate Canada’s war dead. On the second floor, we found ourselves in the Memorial Chamber, which contains The Books Of Remembrance. The name of every soldier who perished fighting for Canada since Confederation is in one of the seven books. Every day at 11:00 am, the pages are turned, to reveal a new list of 90 or so names in each book.

I approached the Second World War Book, hoping to engage my students about the significance of the lists. As I got nearer to the book, I stopped abruptly. It was open on a page containing the names which started with the letter “P.” “What a coincidence,” I thought, but without a doubt, it ended there. I was wrong. As I looked closely, the name on the bottom right side of the page was too clear to deny. Of the 47,000 Canadians killed in the Second World War, that day the book was open on the page listing my mother’s younger brother, WO II Donald Cameron Plaunt. After a few minutes, I regained my poise and shared this incredible coincidence with my students.

…

Every warrior’s life begins in a family. For it is here that he gets his basic training: in self-reliance, relationships, responsibilities and values. He grew up in a loving and close-knit family which gave him the confidence and encouragement that nurtured him for what he became – a generous, fun-loving and mischievous character. Although his nickname was Buggs, he was more like a cuddly teddy bear.

…

Enlisting

At the enlistment centres, recruits signed all the official documents that contracted them to the RCAF. Suitable pilot candidates would continue to flying school and, upon successful completion of two levels of flying instruction in Canada, would proceed overseas for further training in Britain. At any stage of the training, a recruit could be removed from the pilot stream and be re-assigned to further training as navigator, gunner, wireless operator or bomb aimer. Most who enlisted hoped to become a pilot, but the majority were assigned to other roles.

…

After Donald had arrived at the Manning Depot, he wrote to his father: “Well I am here at last…there seems to be an awful lot of waiting around. They really treat you swell around here, not like the old army bull-dogging. The meals, so far, are swell, better than at Ridley. By bad luck, I am to be inoculated tomorrow and thus will be in sick-bay all weekend.” The next day he told his parents: “Things haven’t changed much since yesterday. A bunch of Englishmen arrived and are they ever enjoying the soft life around here. They are terrific fellows and are quite amusing. Saw Mr. Morris (teacher from Ridley) in fatigues dress and I couldn’t help but laugh. Going to phone Bill Lane and hope to see him. I expect to be home on a 48-hour leave in a couple of weeks. Met some Old Boys from Ridley and some guys from Sudbury and aside from waiting, I am having the time of my life.”

…

Overseas

Donald and Syd sailed overseas in March, 1942 and then began further training in two-engine bombers. But the pace of the training and the lack of contact with family and friends made the transition a challenge for him.

As Donald experienced a gloomy phase with not much to occupy him, the Allies scorecard was equally unsettling. 1942 was the low point in the war despite the entry of the Americans on December 7, 1941. The Germans and Japanese were winning in every theatre of the war. By the summer, the Japanese were in control of Guadalcanal and had destroyed the British and Dutch Navies in the Pacific. As well, the Germans thwarted the Canadian attack on Dieppe in August, and the Germans were gaining momentum in North Africa as the first battle of El Alamein had begun. In Russia, the German Army defeated the Russians at Sebastopol and was advancing on Stalingrad. The Battle of the Atlantic was also going poorly for the Allies, as the wolf packs were sinking thousands of tons of Allied ships. But, as Donald predicted, things would be improving by the fall.

…

Although the past several weeks had been a trying time for Donald, a new posting would hopefully lift his spirits. He told his mother that he was pleased that he was heading to Scotland, in his mind, his ancestral home. He was going to an OTU base at Kinloss near the North Sea to train on the Whitley, a two-engine bomber, which would lead to the conversion to a four-engine bomber. He had his heart set on the Lancaster, now considered to be the best aircraft in the British bombing armada. Surprisingly, this information was not cut out, suggesting a slack censor or changing criteria. But there was a precise order to end his last letter from Rissy: “Next time you are in Toronto get a pair of black Oxfords, plain toe-cap and a buckle on them, size ten double E, crepe soles, if possible, and ship them over. I need not tell you to make them good quality ones as you know there is no sense sending ordinary shoes. Will write again soon after I get to my new station next Monday.”

…

Before his posting at Kinloss, Donald had been flying primarily as a solo pilot with an occasional instructor and navigator. At the Scottish base, he was flying bombers which required additional crew: a navigator, wireless operator, bomb aimer, flight engineer and one or two gunners. As in the selection of pilots, all aircrew went through a selection process that began at the Initial Training School followed by instruction in their specialty.

A Lancaster bomber had a crew of seven. Donald was the pilot and the Captain. His crew: (back row) Joe Taylor, gunner; Trevor Williams, flight engineer; Jean-Louis Viau, bomb-aimer; (in front) Jock Lochrie, rear gunner, who was not on the fatal flight on March 12, 1943; and Ralph Franks, wireless operator. The 7th crew member, John Smith, the navigator, presumably took the photo.

Donald travelled to Kinloss with the hopes he would be chosen to pilot a Lancaster. Despite wanting to be a fighter pilot, his character suited him more to be a pilot and leader of a group of men. His family upbringing, his school leadership experience, and his personality combined to make him a natural as a captain of a bomber crew. The success of every operation depended on his capability to fly safely, smartly and with the self-assurance that his crew would feel confident. Along with Donald’s skills as a pilot, he possessed a natural charisma. He was easy going, humourous, generous and most importantly, a competent pilot. He may have had misgivings about things that he wrote in his letters, but his peers only experienced his strengths. Given his gregariousness and social skills, he was a natural for that position. It didn’t take long for his crew to warm up to the man they affectionately called their “Skipper.”

…

The Nissen hut provided a natural habitat to develop a camaraderie that was essential to the creation of a strong crew. The hut was a half-barrel-shaped structure of galvanized metal that provided their living accommodation. Along with beds, there was a coal stove to heat the non-insulated shelter. They worked and played together, as Donald described the scene with his crew to Jean:

Right now my tail gunner, Jock, is batting away at the piano and every now and again is playing Yours which just about makes me weep. Yes, in spite of its antiquity, it is still my favourite piece. One just doesn’t hear any better over here. He was a pipe fitter and is quite a lot of fun and is half mad. But he is a good gunner and a nice chap. He is married and has a couple of children.

The rest of my crew is Canadian. My navigator is an ex-reporter and ex-officer of the Grenadier Guards of Montreal. I hang around with him. My wireless operator is a Jewish kid from Hamilton. He made his living as a horn player in an orchestra. He has us all in stitches all the time. One big laugh. His latest is that if we get shot down over Germany, we tell Jerry his name is Paddy O’Brian so they won’t treat him too rough. My bomb aimer is a French Canadian and was a civil servant and he, too, is a fine chappie. My crew is as mad as they come, so I am happy. All the boys are older than I, and all engaged or married, so I had better be careful of them, or there will be a few people pretty peeved at me. They are all hair brained though and go around calling me “Skipper” whenever they see me within ten blocks. But from that, you can see the great melting pot this outfit is. OK, did I forget to tell you who the captain was?”

He had found a synergistic team, with a proud and happy captain.

…

In writing to his mother on Dec. 17, Donald apologized that he had not written to her for ten days because he was “very busy and on the move.” … He described his surroundings: “Right now it is 6:00 pm and I am in pajamas and bathrobe sitting in my room writing. I just got the fire started and am quite comfortable, and I am going to get caught up on my mail. The weather is bad, and the squadron has a stand-down, so rather than go to town I shall have a pleasant evening “at home.”

Unable to fly, Donald had time to plan his upcoming eight-day leave: “Christmas doesn’t have the same significance over here for me. People don’t enjoy it so much, and then again, I haven’t seen any snow yet. Just fog and rain.” In response to his mother’s question about being a 1st or 2nd pilot, he answered; “I am the 1st pilot and captain, and still I am an almighty sergeant. Not bad eh?”

Dec. 18 ’42 – telegram – sans origin – W PLAUNT LEAVE ON MONDAY FOR CHRISTMAS WITH BILL MAY YOU ALL HAVE A VERY HAPPY ONE ALSO THE PARTY ON NEW YEAR’S IS AS GOOD AS EVER LOVE DONALD PLAUNT

On December 25th, Donald wrote a joint letter to his parents: “Well, here it is Christmas, and although it isn’t anything like the good time we have at home, it isn’t too bad considering. As you probably know by my cable of Dec. 22 I am on Bill Lane’s base for my leave. Unfortunately, I couldn’t have Christmas dinner with him as he is now a pilot officer and I don’t belong! It is too bad, but it can’t be helped! In spite of everything else there seems to be no shortage of liquor and everyone, excluding me of course, is quite inebriated, “ye olde English spirit,” you know.”

Despite the uplifting spirit that Christmas usually brings, the two Sudbury friends were feeling disheartened. They had just learned that Syd was reported missing over France on December 9 on a return raid from Turin, Italy. “Christmas for Bill and I is somewhat dampened due to Syd’s absence. However, we are quite confident he will turn up as a prisoner or make a clean escape from France as it isn’t too tough a proposition.”

…

When he arrived back at the base on Dec. 30, he was astounded at what Santa had brought him. Donald was quick to tell his mother of his good fortune:

Well, you can imagine the mighty pleasant finale to an excellent leave when I arrived back here and found twenty-one letters waiting for me and four parcels. … I am writing this under the greatest of difficulty. You remember, I told you that my wireless op was a horn player, well my flight engineer turns up with a guitar, so they are both hammering away. Well, tomorrow night is New Year’s Eve, and I am thinking of the swell times we had on that date and on Jan. 1st, I hope you have the usual time “at home.” I will celebrate my New Year’s at 6 am Greenwich time and at 12 pm Sudbury time, the same time as you will.

Well, Mom, I have been flying tonight, and it is getting quite late so I must say goodnight for now as I could use a bit of shut-eye. Write soon and often. I will answer your letters next time I write. A very, very, Happy, and again I say, Victorious New Year Mother.

…

On New Year’s Day, he wrote to his youngest sister Jean:

Bonne Annee, ma petite soeur! In other words, it is New Year’s Eve and I am celebrating it by writing to you and a few other chosen ones. Boy, would I like to get in the necking and mugging you will tonight, and here I am cooped up 1,000,000 miles from nowhere, with only O’Brian (Ralph Frank) to kiss in bringing in the year of the great and final victory. On taking a good look at him, I’ve changed my mind and will kiss no one.

Aha, so your loved one is off to the wars, my beauty, no doubt he received Lovelace’s old line about “I could not love thee dear so much, Loved I not honour more?” Boy, see what education does for one! What is the wee lad going to be, pilot!

…

Last Mission

On the night of March 12, Donald participated in a second mission to Essen. For Donald, it would be his eleventh mission, his sixth in the past nine nights. On the raid to Essen that night, 97 Squadron contributed eleven aircraft to a stream of 457 bombers that attacked the key industrial centre of the German Reich. Three Lancasters of the 97 had to return due to technical failures. The principal target of the operation was the Krupp factory just west of the city centre. Donald and his crew either left the plane or crashed landed near the town of Wulfen, 25 kilometres north of Essen.

…

On March 14, 1943, Donald’s family received a telegram:

REGRET TO INFORM YOU ADVICE HAS BEEN RECEIVED FROM THE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE CASUALTIES OFFICER OVERSEAS THAT DONALD CAMERON PLAUNT IS REPORTED MISSING … RCAF CASUALTIES OFFICER

…

Believed to Be Killed

On May 9, the Plaunt’s received a second telegram confirming their worst fears. Donald was “reported missing believed to be killed overseas.” The “luck of the Plaunts” had run out.

…

Frustrated with the incorrect information (another man was reported as the pilot) in the first letter from Donald’s Wing Commander, WB began to enquire through his connections. He contacted his cousin, FX Plaunt, of Montreal, whose nephew, Frank Wait, was posted at the RCAF headquarters in London. On May 6, Wait responded that news had been received by the Red Cross that Donald was the captain of the Lancaster, but that only two of the three Canadian crew had been identified and buried. There was no information on Donald, nor of the four RAF crew members. Wait concluded: “From the information we have, it is most difficult to say what happened. The two chaps that were found may have bailed out and were killed on landing, or they may have been the only two identifiable after a crash. On the other hand, they may have been the only two who died in the crash, and the rest of the crew may have escaped or have been taken prisoner.”

…

Missing Remains

Although Donald’s mother accepted his death, the seeds of doubt continued to fester within his father concerning the circumstances surrounding Donald’s death. Soon after the war was over in Europe, he asked Al Flood, a good friend of his daughter Helen and a corporal in the RCAF, to visit the Wulfen cemetery to verify what the RCAF had told the Plaunts regarding the burial of Donald. On August 7 Flood wrote more disturbing news:

At my first view of the cemetery I was greatly put out at its condition but was soon put on the right track when I contacted the British Army unit in Wulfen. A good part of the cemetery had been bombed and suffered three or four direct hits. The cemetery is not big by any means, so you can readily imagine the damage. I looked high and low for Donald’s grave but failed.

…

Flood’s photo of Wulfen cemetery: from L to R, markers for Viau, Williams, Dillon and Smith

…

Donald’s mother was remarkably accepting of Donald’s death and on May 11 she wrote her mother and sister Pearl of the heartbreaking news.

This will just be a short note, with not very happy news. We had a wire from Ottawa on Sunday evening saying that Donald had lost his life on the night of March 12, so reports the German Red Cross.

So that’s final…

WB and I went up to Wye Saturday and home Sunday. Awful Lonesome. I would see Donald tearing up the path and shouting “Where do we eat?”

Love to all,

Mildred

…

His School Remembers

Donald’s death had a profound impact on his Ridley friends and teachers. John Sale, a classmate of Donald’s, remembered that Porky was one of the first Ridleians to die whom the boys at the school knew. His death brought a poignant reminder of the grim reality of war. There were fine tributes to their admired Porky (his Ridley nickname) in Acta Ridleianna, and in letters from his Ridley teachers to the Plaunts. He had spent his formative years there and had developed a special relationship with the school. An obituary in the Acta (Midsummer ’43) was a meaningful tribute to one of their own:

Seldom has the School been so shocked and filled with a feeling of personal loss, as many of the boys still at the School remember “Porky’s” familiar figure on the campus. Don came to Ridley from Sudbury in September 1937, a total stranger to everyone, but it was not long before his cheerful disposition and happy smile had won him a host of friends. He quickly absorbed the spirit of Ridley and early in his school career displayed qualities of leadership, which steadily developed during his four years at the school. He took an active part in all School activities. It would be difficult to conceive of anyone who could do more for the morale of a crew than Donald Plaunt. In his heroic death, Ridley has lost a fine Old Boy, one who had he lived, was destined to make his mark in some line of endeavour. If he had to go, we know that he would not have chosen any other way than that of doing his duty to his country and his School.