Article written for the Ontario Professional Surveyor, Volume 54, No. 4, Fall 2011 OPS, Vol.54

Few Canadians appreciate the importance of surveying in the development of Canada. I seldom came across the topic in the Ontario curriculum as a history teacher for more than thirty years. There were a few exceptions: the Riel Rebellion in Manitoba, which resulted from the federal government’s survey of the Metis lands; David Thompson’s extensive mapping of the North West, and Sir Sanford Fleming’s surveying of the Canadian Pacific (CPR) transcontinental railway.

My limited knowledge of surveying changed when I began to research the history of Lake Pogamasing in Northern Ontario where my family has had a summer residence for seventy years. Lake Pogamasing is located in the Sudbury District, some 85 kilometres north-west of Sudbury alongside the CPR mainline and the Spanish River. After retiring from teaching, I wanted to write a history of the lake and the region. What amazed me was that this small lake witnessed so many of the notable Canadian developments in the 19th and the first half of the twentieth century: an Aboriginal community, a Hudson’s Bay Company post, the building of the first transcontinental railway, logging pine for fifty years, a sawmill operation during the Great Depression, and tourism based on trout fishing after the Second World War. The area was a microcosm of the evolution of the Canadian wilderness.

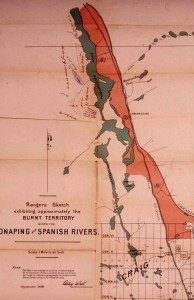

Surveying was not one of the topics I initially considered for my book, but that soon changed when I came across a number of interesting reports, drawings and maps of the early surveyors’ work in the Archives of Ontario. In addition, I found this map created by the Department of Crown Lands in preparation to auction off a burnt limit along the CP line because of a massive forest fire in 1891. I also discovered some relevant survey documents such as the instructions given to the Code brothers of Cobalt in 1911to create the townships in the Pogamasing area. I was encouraged by the archive staff to go to the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) in Peterborough as this is where most of the records were located.

Surveying was not one of the topics I initially considered for my book, but that soon changed when I came across a number of interesting reports, drawings and maps of the early surveyors’ work in the Archives of Ontario. In addition, I found this map created by the Department of Crown Lands in preparation to auction off a burnt limit along the CP line because of a massive forest fire in 1891. I also discovered some relevant survey documents such as the instructions given to the Code brothers of Cobalt in 1911to create the townships in the Pogamasing area. I was encouraged by the archive staff to go to the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) in Peterborough as this is where most of the records were located.

Off I went to Peterborough where I met Allan Day, the manager of the survey records for the Ministry. Anyone who has been to this department will remember Al, now retired. He was a gold mine of information and helpfulness in finding me the maps, township files and survey reports of the Pogamasing area. In addition, he recommended two books, They Left Their Mark and Renewing Nature’s Wealth that provided useful insights into the very comprehensive nature of the surveyor’s task. I quickly came to understand the essential work they accomplished in the opening and development of Northern Ontario.

A third source of information for my research was the Annual Report of the Association of Ontario Land Surveyors. From these I could see that at the association’s annual meetings, veteran surveyors shared their experiences with the younger members. What intrigued me most about their reports were the detailed descriptions of their working conditions. They worked in all seasons, usually in very remote areas, for months at a time. Surveying parties consisted of a surveyor, to manage the project; a cook, possibly a forester; and any number of axemen and chainmen to cut and measure the line, with a 66 foot chain prior to 1900.

One of the more prominent surveyors at that time, Alexander Niven, described what it was like to work one winter in the early 1900s. They required snowshoes every day until the middle of April and lived in tents with only an outside fire for warmth. “Our food was of the usual kind for surveys in the early days — flour, pork, beans, split peas and tea, with a little sugar for the exclusive use of the cook. We carried a muzzle-loading rifle and shot a caribou, caught a few fish through the ice, and I remember that we shot 76 partridges with a horse pistol during the winter.”

Surveyors hired Aboriginal men as guides, axemen or packers. They were sent miles ahead, without maps, to find and set up camp on “the edge of a small lake just about where the line will cross” while the daily survey was conducted. These scouts had a strong sense of direction and awareness and were very accurate navigators. When the survey party was about to finish the day’s work, a gun was fired to alert the scouts and within 20-30 minutes they would meet the survey crew. On one occasion, surveyor T. J. Patten reported that when they arrived at camp, the Native had been so precise that he had to take his tent down as it was on the line.

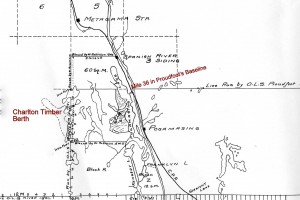

It was in the reports and drawings from the Peterborough archives where I found the important details of the surveyors’ work in the Pogamasing area. Hume B. Proudfoot, a civil engineer graduate from University of Toronto, conducted the initial baseline survey of the area in 1888. He surveyed a 42 mile baseline from Roberts Township, approximately 36 miles due east of Lake Pogamasing, crossed the recently completed Canadian Pacific rail line, the Spanish River and finished six miles west of Lake Pogamasing (last three miles illustrated in this map). All subsequent surveys in the area cited Proudfoot’s baseline as their reference line and his baseline constituted the border between 14 townships. Other surveyors (Speight, DeGurse and Robinson) completed township surveys south of the Pog area. There were only minor variations in the surveyor’s observations as their reports echoed common characteristics of hilly terrain, good pine, plenty of water and poor agricultural possibilities. Speight did report on the mineral possibilities in Stralak Township, but the results were insufficient to open a mine.

It was in the reports and drawings from the Peterborough archives where I found the important details of the surveyors’ work in the Pogamasing area. Hume B. Proudfoot, a civil engineer graduate from University of Toronto, conducted the initial baseline survey of the area in 1888. He surveyed a 42 mile baseline from Roberts Township, approximately 36 miles due east of Lake Pogamasing, crossed the recently completed Canadian Pacific rail line, the Spanish River and finished six miles west of Lake Pogamasing (last three miles illustrated in this map). All subsequent surveys in the area cited Proudfoot’s baseline as their reference line and his baseline constituted the border between 14 townships. Other surveyors (Speight, DeGurse and Robinson) completed township surveys south of the Pog area. There were only minor variations in the surveyor’s observations as their reports echoed common characteristics of hilly terrain, good pine, plenty of water and poor agricultural possibilities. Speight did report on the mineral possibilities in Stralak Township, but the results were insufficient to open a mine.

The problem of forest fires was constantly mentioned in surveyor’s reports. For example, Proudfoot observed that: “Nearly all the country crossed by this line has been burned at different times, some very recently, and other parts a great many years ago.” Forest fires were more frequent then, as the government did little in the way of fire prevention, or to initiate action to extinguish them. Proudfoot’s remarks on the ubiquitous nature of forest fires was confirmed by Elihu Stewart, who created 20 townships along the CPR mainline north of Pog in 1891 and found that “the greater part of the country passed over was ruined by fires, killing most of the timber.”

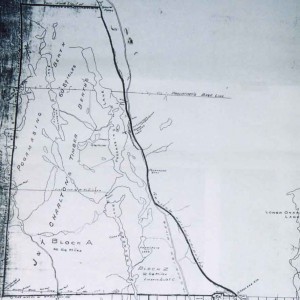

The other important function of the surveyors in this area was to generate timber berths as lumbermen were eager to get access to the Spanish forests opened up by the CPR in 1884. The huge fire of 1891, as illustrated by the previous map, forced the government to open the area sooner for fear that the bugs would destroy the pine. Consequently, logging began in the fall of 1891 after an auction of the burnt limits. The following year A. J. Whitson created the first timber berth on the west shore of Lake Pogamasing. Further surveys around Lake Pogamasing led to the creation of a 120 square mile timber berth that became known as the Charlton Limit named after the first lumberman to log it.

By 1911 most of the meridians and baselines were complete and it fell to the Code brothers, mentioned earlier, to complete the missing lines to create townships. Besides the drawings which led to the township map drawn by the Codes, the other interesting aspect of the surveyors work was the first reports of the area’s topography, wildlife, timber species, and waterways.

As well as the land surveying conducted by the Ontario government, geological surveyors employed by the federal government assessed the area for minerals. William Bell was one such surveyor who drew the first map of Lake Pogamasing and other waters in the area. Given that there has been very little mining activity in the area suggests his reports were not favourable to the possibility of minerals.

Proudfoot, Niven et al were instrumental in the opening of Northern Ontario by charting the unknown territory opened by the railroad. In addition, their reports encouraged lumbering and discouraged mining and agriculture in both the Pogamasing and wider area. My fascination with their work and appreciation of their vital work led me to include a chapter on surveying in my history of Lake Pogamasing. As well as surveying, I highlight the roles of Chief Louis Espagnol as the Aboriginal manager of the Hudson Bay post on Pogamasing, and W. B. Plaunt, my grandfather, who operated a sawmill operation there before and during the Great Depression.

Drawings and maps courtesy of the Archives of Ontario and the Ministry of Natural Resources

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Hello, I simply wanted to take time to make a comment and say I have really enjoyed reading your site.

Hi Andy,

I’ve enjoyed reading this article on surveying and other excerpts from your book. Pog is more real for me now since I’ve visited the lake and your property with John Stanyon several years ago. It’s great that you devote so much of your retirement to doing this research.

Thanks,

David

Hi David,

Thank you for your note. I just feel so fortunate that I have found something that I enjoy doing and sharing and that there are people like you who also enjoy it.

Have you seen the video on lumbering at Pog I posted today?

All the best,

Andy